16 Jun Father torments himself after losing his son to an opioid overdose

Andy Hopson had dreams of building a recovery home with his son Dakota. That never happened.

Mandi Wright, Detroit Free Press

DETROIT – Is it love?

Is it guilt?

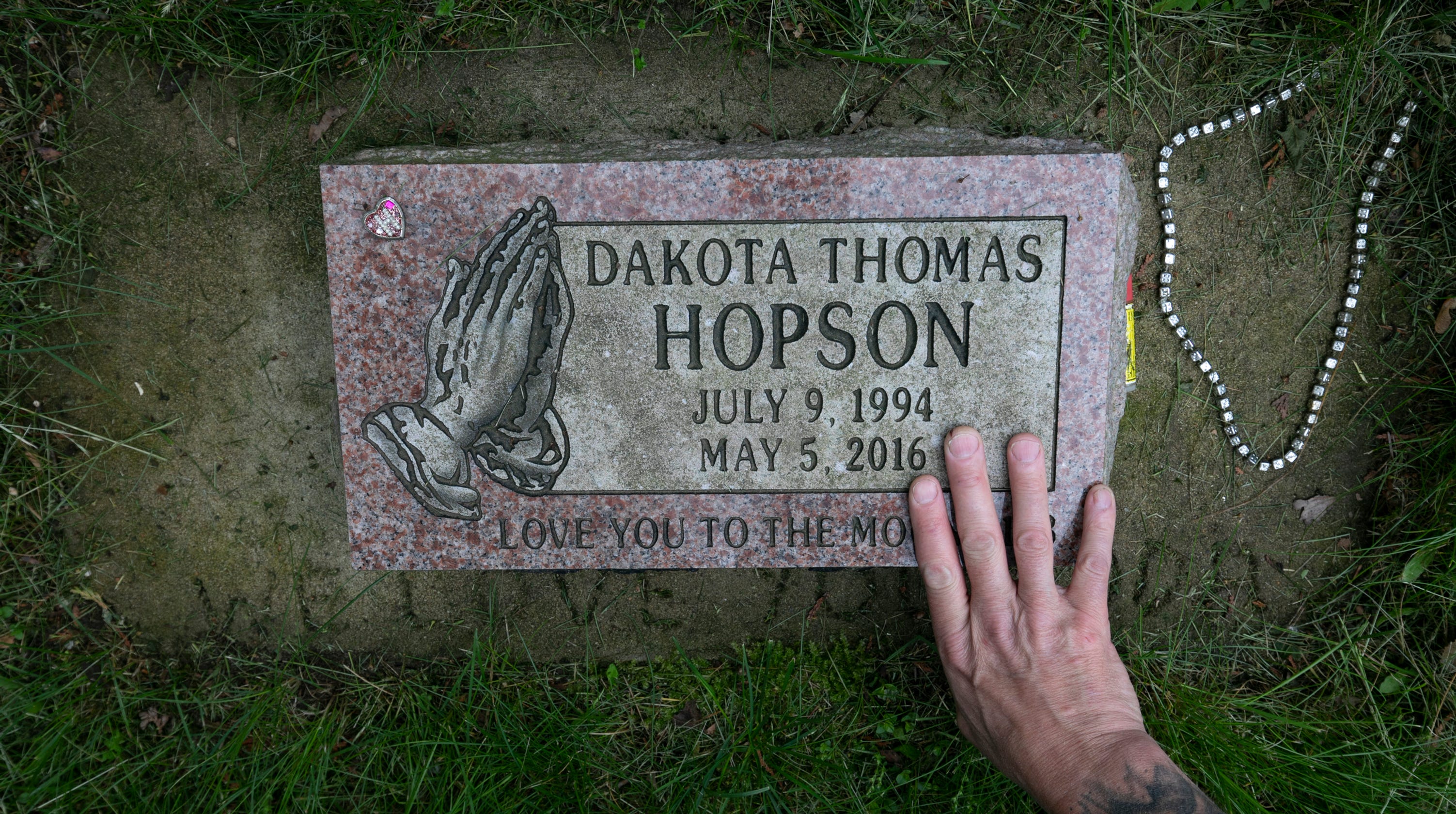

Is it a little – or maybe a lot – of both that Andy Hopson feels in the early mornings when he kneels on the cemetery’s cool, dewy grass, leans forward and kisses his son’s gravestone?

How about when he adds to his body another tattooed tribute?

Or when he stands before an audience of hundreds of people, flawed, nervous as can be, and testifies about the horrific things that drugs did to his boy?

Because Andy knew from his own experience as a recovering addict what Dakota Hopson – his son with the wide smile, his son who played rap music so loud the house shook – was doing that night three years ago.

Holed up in a corner room at the Howard Johnson’s by Detroit Metro Airport, the kid was doing what most addicts do: having one last party before going back to rehab. He was shooting heroin, soaking in the poison that made him feel so good.

Was Andy worried? Of course. Dakota, 21, was incredibly high – Andy heard it in his voice when they spoke on the phone, the way he mumbled, his words slow and groggy. “Dude, you’ve got to stop,” Andy remembers saying. “You’re so high right now, you’re going to die.”

Yes, Andy started driving to the hotel to check on Dakota. But really, what good would that do? Dakota would be angry with him for ruining his high. He’d refuse to come home. I don’t want to trouble you, Popps, Dakota had said when he insisted on checking into a hotel for the night, though Andy suspected all that was more about finding a place to get high without being hassled than being concerned about imposing on family. Besides, Dakota swore to Andy that he was fine. He was with his people, nothing bad would happen. So Andy turned around and went home.

Opinion: The tools dad left me can’t fix my broken heart on Father’s Day

‘I can’t help but cry’: Moving past tragedy, family celebrates two dads on Father’s Day

All his boy needed to do was ride out the night and get to rehab in the morning. It’d be a fresh start. He’d get clean again, he’d be able to spend time with his kids, find a job and live a good life.

But by morning, Dakota was gone; dead from a mix of heroin and fentanyl, one of 1,762 people in Michigan to die from an opioid overdose in 2016.

And Andy, after screaming and crying and punching the wall of the hotel room where he found Dakota crumpled on the floor with vomit on his face, was stuck wondering what if. What if he’d gone to the hotel that night? What if he’d made Dakota stay with him, or stayed with Dakota himself? What if he’d been a better father to his son?

“That’s something I have to live with forever,” says Andy, who is 51 and lives in Livonia.

This is a story about an anguished man trying to make peace with what he did – and didn’t – do for his son. And about finding something quite unexpected along the way: redemption.

Memories are everywhere

Andy doesn’t like this time of year, the spring and early summer months, when birds chirp to signal the beginning of each new day and flowers bloom and everything comes alive.

May 5 is the anniversary of Dakota’s death.

July 9 is Dakota’s birthday.

And Father’s Day, the saddest day of them all as far as Andy is concerned, is smack in the middle. “If God came down here and said, ‘It’s either you or him,’ I would say, ‘Take me.’ ” … “Your kids,” he says, “aren’t supposed to die before you.”

Andy always wanted to be a good father. But he’s also the first to admit there are plenty of times he failed, showing more interest in his crack pipe than his kids.

‘It was just a horrible, horrible morning’: Two brothers, hockey players, died on same day of opioid overdose.

‘Very sad’: Columbine survivor Austin Eubanks died of accidental heroin overdose, coroner says

Addiction is a part of Andy’s family: it hooked his grandfathers, his father, his brothers, his sister, his sons, just about everyone, except his mother. To her, a young Andy, disgusted by the falling down drunks around him, swore, “I’ll never be like them.” He had a plan – escape the family curse by playing baseball. He played Little League and he played on school teams. But by the time he turned 16, his fascination with the sport was waning.

In its place, alcohol. Despite his promise to his mother, Andy started drinking. Peach schnapps and vodka, that’s what he took to weekend parties with high school friends; he loved the way the liquor made him feel, all warm inside. He started smoking weed, too. He didn’t really like it, but everyone else seemed to and Andy didn’t want to stand apart from the crowd. He liked being popular. At 17, Andy tried cocaine and before long he was in deep; cocaine made him forget how angry he was about his parents’ divorce and how awkward and insecure he felt around others. It made him feel like he could do anything. He graduated from Romulus Senior High School in 1986, got a job as a hi-lo operator and fell into a routine: drink, snort, work; drink, snort, work. When he had a falling-out with his cocaine connection – he moved in on his dealer’s girlfriend – Andy tried crack. The high he got from the rock didn’t last as long as the powder, but man was it intense. He lived for that high.

It’s true, Andy managed brief episodes of sobriety. He got married during one of those periods in 1994, adopted his wife’s son and had another, Dakota. They looked so much alike, those two, Dakota and Andy. Same smile, same eyes. Years later, people would mistake an elementary school snapshot of Andy – clad in a turtleneck and plaid pants, the unofficial uniform of the 1970s – for one of Dakota. And when Andy had Dakota’s face tattooed on the inside of his forearm in tribute to his lost son, a friend wondered why he’d gone ahead and gotten a tattoo of himself. “That’s not me,” Andy said. “I’m not THAT vain!”

Andy and his kids did have some good times. He remembers the times they went swimming together and to movies; he remembers installing a baby seat on his bicycle so he and Dakota could ride together.

But drugs always crept back into Andy’s life. And when they did, Andy was off and running, powerless to do anything except chase that high. He and Dakota’s mom split up in 1996. He saw their kids on weekends and thought he was a good father, though now he admits that he couldn’t wait until the kids went back to their mother’s house so he could start drinking again.

“I didn’t bond,” he says. “Emotionally, was I there? No. It took me a lot of years to admit that.”

Eventually, Andy dropped completely out of the kids’ lives. He regrets greatly that he didn’t see them for three or so years. “Guilt and shame and sadness is what I feel,” he said recently.

Andy sunk even deeper into drugs and alcohol.

‘Deaths of despair’: Deaths from drugs, alcohol and suicide hit young adults hardest

When he wasn’t in jail for drunken driving or probation violations, he lived on the sofas of friends and relatives. When he got fired from his job, he went to work in restaurants, and because he’s personable and generally a hard worker, he earned plenty in tips – quick cash for drugs. And when he lost those jobs for being too drunk or high to work, he started stealing.

Armed with a BB gun, Andy robbed people at ATM machines. He points out, with some relief, that he “still had a conscience” because when people talked back to him or refused to give up their money, he’d just walk away. Once, on a bicycle because he no longer had money to keep a car, Andy rolled up to the window of a drug house – a drive-through of sorts – got what he wanted and took off without paying. Even now, he’s amazed he wasn’t killed along the way. And he wonders: How did he manage to escape death from drugs when Dakota did not?

In 2001, Andy had another son, Drew, with a woman he met through the Alcoholics Anonymous meetings he was required to attend as part of his drunken driving probation. They got married; he left his newly sober wife alone on their wedding night so he could get high. When she threatened divorce, Andy got clean.

He also threw himself into Alcoholics Anonymous for real, sponsoring others, offering counsel, and when necessary, a place to stay. “I was that guy who would hear someone at the table was homeless, I’d say, ‘Just come stay with me,’ ” Andy remembers. “It just became natural with me to help.”

Finally, Andy seemed to be in a good place. Though he split from his second wife, he did so amicably and they remain close friends. (“When we got sober and learned who we really were, we really didn’t have a lot in common,” says Shannon Hopson, who is 45 and lives in Northville.) Andy was working. He also was trying to repair his relationship with his kids from his first marriage.

They were a mess – Andy’s adopted son was struggling with drugs; he’s currently in prison serving 8 to 30 years for attempted murder. And Dakota was experimenting with marijuana, trying to be all gangster, and getting into fights at school and telling teachers to “f— off.”

Opinion: I shouldn’t have been ashamed of my brother. Eliminate the stigma around opioid addiction.

While he could be charming and a practical joker – he’d put Saran wrap on the toilet so whoever was using the bathroom would pee on themselves or on the floor – Dakota also could be manipulative.

“He’d try to play all the parents against each other,” Shannon Hopson remembers. “Whoever he could get something from, that would be the one he would be all about in that moment.”

Dakota moved in with Andy.

And then, in 2008, total disaster: Andy and his girlfriend, whom he’d met through his second wife, relapsed. They went to a bar for a friend’s birthday party, got cocky and figured they’d had enough years in recovery to handle one drink. But that led to many. And that led back to crack. Every night after work, they retreated to the bedroom of their Northville townhouse to drink and get high while the kids who stayed with them – his kids, her kid – went unchecked.

The relapse lasted a little over a year until one morning Andy saw that Dakota – who liked nice things and brand names – was wearing shorts with holes to school. And right then, Andy realized how horribly he was failing as a father. His kids deserved better.

By late 2009, Andy was sober. His girlfriend – who became his third wife – got sober, too.

Aside from one slip almost five years ago when he smoked crack in his garage while she was away, Andy has maintained his sobriety.

Before long, he was trying to maintain Dakota’s, too.

‘I know you’re doing heroin’

Day after day, they had the same argument.

“I know you’re getting high! I know you’re doing heroin!” Andy would say to Dakota. “Why don’t you just get honest with me?”

“I’m not!” Dakota always countered.

Dakota – who became a father in 2011, the day before his 17th birthday – was already into pills and alcohol and weed, which he also was selling. And now his friends were telling Andy that Dakota was looking for “dog food.”

“What’s that?” Andy asked, only to be told it’s slang for heroin.

Finally, sometime in 2014 – Andy doesn’t remember exactly when – after months of questioning, Dakota admitted the truth: He was a heroin addict.

And Andy – who had talked and talked about how dangerous drugs are, how powerful addiction is, how much he didn’t want Dakota to make the same mistakes he’d made – went to work trying to save his son. I wasn’t here when he was younger, Andy decided, but I’m going to be here for him now.

Over the course of two years, Andy helped Dakota get into rehab. Andy helped him find apartments and sober living houses, where addicts are required to attend 12-step meetings such as Alcoholics Anonymous or Narcotics Anonymous and are forbidden from using drugs or alcohol. Andy helped bail Dakota out of jail once; another time he drove Dakota to the police so he could turn himself in. Andy bought Dakota cigarettes, lunch, whatever he needed. But he never gave Dakota cash. Andy knew better than to give money to a drug addict.

Andy tried tough love. He vowed not to pick up Dakota in the middle of the night when he said he had no place else to go. But he always relented. “I’m not going to wake up and know that my kid froze to death because I wouldn’t let him sleep on my couch,” Andy said.

On Father’s Day 2015, when Dakota was dope sick – sweating, throwing up, cramping – because he hadn’t had any heroin, Andy drove him to a drug house and bought him Suboxone (generic: buprenorphine), a medication doctors use to soften addicts’ withdrawal and reduce heroin cravings.

“I just wanted him to have a good day with his daughter,” Andy says.

Through it all, Andy could feel the two of them growing closer. One day, while they were sitting together on a bench in front of an apartment building where Dakota stayed, Dakota laid his head on Andy’s lap and cried: “I don’t want to live this way. I just want to die. I can’t quit. I can’t go through this no more.”

“I get it,” said Andy, who had, in the midst of his own addiction, also thought about killing himself. “That’s why you need to go to detox.”

In the late fall of 2015, Dakota made another go at rehab, this time in California, and Andy was thrilled. (“He really wants this,” he said.) Dakota got clean and returned to Michigan early in 2016. A month or so later, when he started using again, Dakota went back to California only to return to Michigan after a few weeks, at the beginning of May.

He said he wanted to go to a rehab closer to home so he could see his baby son and preschool-age daughter more often. He wanted to spend holidays with them.

And Andy, who had missed so many holidays with his own kids, understood.

He found a place for Dakota that was an easy drive from home, but Dakota died before he could check in.

“It was the worst day of my life,” Andy says.

Keeping his memory alive

On a pleasant day in May, Andy – wearing a dog tag with a copy of Dakota’s fingerprint on it and dozens of commemorative tattoos – stood in front of hundreds of substance abuse counselors and social workers gathered at a conference center in Livonia and told Dakota’s story. He told his story. He told their story.

He was there on behalf of Families Against Narcotics, a group that works to educate people about opioids and addiction and provide support for families impacted by substance abuse.

And as uncomfortable as it makes him to talk in front of a crowd or do an interview, Andy believes sharing the experience he had with Dakota can prevent others from falling in with heroin. It’s what he does, when he’s not working 70 hours a week at a slag processing plant.

Andy gets emotional sometimes – he might pull Dakota’s driver’s license from its place in the glove box of his truck and look at it for inspiration, he might tear up, he might step away from the microphone and cry.

But that’s OK because Andy’s doing what he struggled to do for so long: He’s being a good father to his son, taking care of his kid the best he can now, making sure he isn’t left behind or forgotten. And that makes him feel good.

“I don’t think people realize that by talking about him, you’re keeping him alive,” Andy says.

That’s all he ever wanted, to keep his kid from dying.

Follow Georgea Kovanis on Twitter: @georgeakovanis

Read or Share this story: https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/nation/2019/06/16/father-torments-himself-over-son-opioid-death/1471248001/

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments