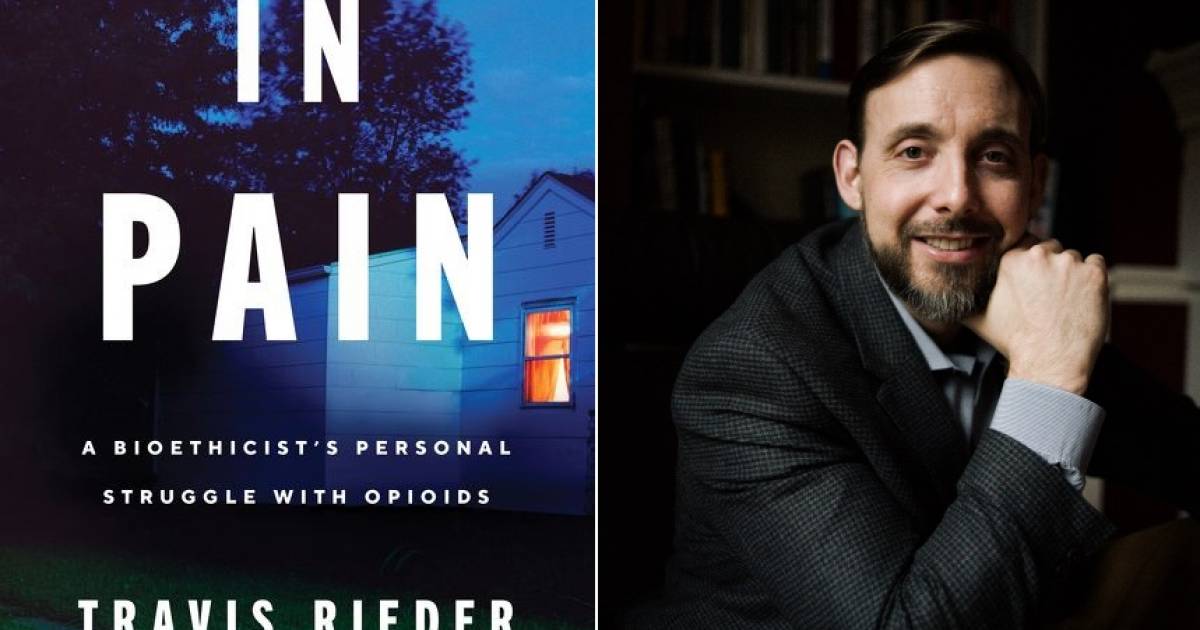

17 Jun Travis Rieder’s book In Pain examines the overdose crisis with the unique insight of bioethicist dependent on opioids

Travis Rieder has bleak outlook on the current state of America’s overdose crisis. The author of In Pain: A Bioethicist’s Personal Struggle With Opioids told the Straight that not only have authorities failed to reduce deaths, they’re also badly hurting people with their attempts.

In a telephone interview, Rieder explained that the epidemic that killed some 72,000 people in America in 2017 and roughly 4,000 in Canada was once largely driven by prescription opioids. And so regulators and law enforcement cracked down on doctors overprescribing addictive pain medications like OxyContin and Dilaudid. The problem, Rieder said, is that authorities continued with that response after it stopped working and despite its negative unintended consequences.

“We did actually slow overdose deaths from prescription opioids,” he noted. “But it didn’t slow the opioids crisis. It actually exacerbated it.

“Overdose-death rates have skyrocketed since then, and now we have this heroin and illicit-fentanyl crisis,” Rieder emphasized.

The crackdown on prescription painkillers has left doctors significantly less likely to prescribe opioids to patients who truly need them, he continued.

“We’re sort of in the worst possible moment here when you think about the Venn diagram of pain, opioids, and the opioids crisis,” Rieder concluded. “We made everything worse without solving anything.”

America is not experiencing an overdose crisis, Rieder thus maintained. Rather, it is a “crisis of pain management”, where people who need opioids are not receiving them and are left in pain, and people who do not need opioids have found too many and are dying of overdoses.

Rieder is uniquely qualified to reassess America’s opioid epidemic and critique the government’s response. In addition to his work as a bioethicist at Johns Hopkins University, where he’s a research scholar and director of the school’s master of bioethics program, he has struggled with opioids himself.

As he recounts in In Pain, which hits bookstores Tuesday (June 18), Rieder was badly injured in a 2015 motorcycle accident. His left foot was crushed between his bike and a van, requiring a half-dozen surgeries and sending Rieder through many facets of the health-care system that he had spent his career studying as an academic.

The pain was often unbearable and, in different combinations at various times, Rieder received morphine, OxyContin, immediate-release oxycodone, hydromorphone, and fentanyl. He describes these opioid-based medications as a godsend, but one which, for some people, comes with great risk.

Rieder never became addicted to opioids. He didn’t crave the warm sense of euphoria that drives so many to seek street drugs like heroin. Rieder became dependent on the opioid medications that doctors prescribed for his injured foot. When he began to reduce his intake of the drugs, he felt torturous physical and mental symptoms, becoming ill, severely agitated, and depressed. The excruciating experience is meticulously documented over 21 pages.

“For me, the sickness started within a day of the first missed dose,” he begins in the book.

“The flu-like symptoms dialed up in intensity to a level that I really didn’t think was possible,” he writes about day six. “I would sweat profusely while lying in the cold of the air conditioning; and yet, if I managed to force myself outside, I would be covered in goosebumps while sitting in the hot summer sun.

“The difficulty sleeping ramped up significantly,” he continues. “I no-longer felt merely alert—I was jittery, and often, if I lied down to really try to sleep, my limbs would start to feel like they needed to be moved; I found myself kicking, squirming, and shaking constantly. The result is that I would spend more and more time just lying on the couch, sweating, shivering, jittery, not sleeping but exhausted.”

The following week, Rieder is crawling to the toilet in tears, his stomach heaving but unable to vomit, depressed to the brink of suicide.

On the phone with the Straight, Rieder said he shared those moments of such vulnerability because he wants health-care professionals and members of the general public to feel empathy for anyone who is going through something similar.

“I got my foot blown apart by a van running into me and the worst moments of my life were not that; they were withdrawal,” he said. “I want people to understand that opioid withdrawal is not ‘uncomfortable’. Opioid withdrawal is enough to drive someone to consider killing themselves.”

During those weeks of utter despair, no one would help him.

Rieder and his wife repeatedly called every single physician and specialist who had worked on his foot during the preceding months. No one offered a solution. One nurse directed him to a drug-rehab facility. Upon hearing he was now struggling with an addiction, some doctors refused to even speak with him.

It was this aspect of Rieder’s long and numerous interactions with the health-care system that stuck with him and led him to write In Pain.

In the book, he points out that when a health-care professional does something that causes a negative outcome in a patient, they are generally expected to take ownership of that outcome and provide the patient with a response.

“Given that infection is one of the most consequential risks of undergoing surgery, surgeons go to great lengths to minimize the risk and then act quickly on any infection that does occur as a result of the procedure,” he writes. “If an infection does occur and progresses beyond the abilities of the surgeon, she gets infectious disease specialists involved. Surgeons see both harm mitigation and a smooth handoff as part of their responsibility.”

Why is it different with addictive pain medications that can lead patients to experience brutal symptoms of withdrawal?

“One of the things that we definitely have to do is assign responsibility for patients in a way that helps physicians and clinicians understand where their responsibilities lie,” Rieder said on the phone. “You need somebody within the health-care system to take responsibility for a bunch of work that usually just doesn’t get done.”

There is a growing awareness of that need, he added, but how it should be met remains a matter of debate.

“We’re probably not going to pay an orthopedic trauma surgeon or a plastic surgeon to do long-term pain-care follow-up, which means there needs to be some kind of creative structural solution that each health-care system or each outpatient centre needs to put somebody into that role,” Rieder said.

That’s his ultimate goal with the book, he added. “That it really becomes incumbent on health-care systems to say, ‘Yes, that is totally sensible. We would be to blame if we acted like this wasn’t a problem.’”

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments