28 Apr Canadian hospitals reported 138 cases of lost fentanyl in one 15-month period, federal records show

Vials and patches of fentanyl were reported missing from Canadian hospitals at a rate of about twice a week over a 15-month period ending on Jan. 1, 2018, according to federal records obtained by the Star.

In total, the records reveal 138 incidents of lost fentanyl, including cases involving the even stronger derivatives remifentanil and sufentanil in patch and liquid forms.

It’s not clear how many of the highly dangerous opioids reported missing from hospital shelves were stolen or thrown out, as the causes for the disappearance are not be captured in the figures.

In many hospital drug theft cases, the missing drugs are stolen for personal use by staff, according to experts.

Seventy-six of the 138 incidents occurred in Ontario, while Alberta had the second-highest reported rate of missing fentanyl with 21 incidents, followed by Quebec with 20 and British Columbia with 11, according to the data, obtained under the Access to Information Act.

Nunavut had only one incident but it was significant: 20 packages of fentanyl missing from a break-and-enter at a nurses station in May 2017.

The total amount reported missing included more than 600 millilitres worth of injectable fentanyl and more than 50 packages of the drug. (The size of each package is not revealed in the data, making it impossible to estimate the full quantity of missing fentanyl.)

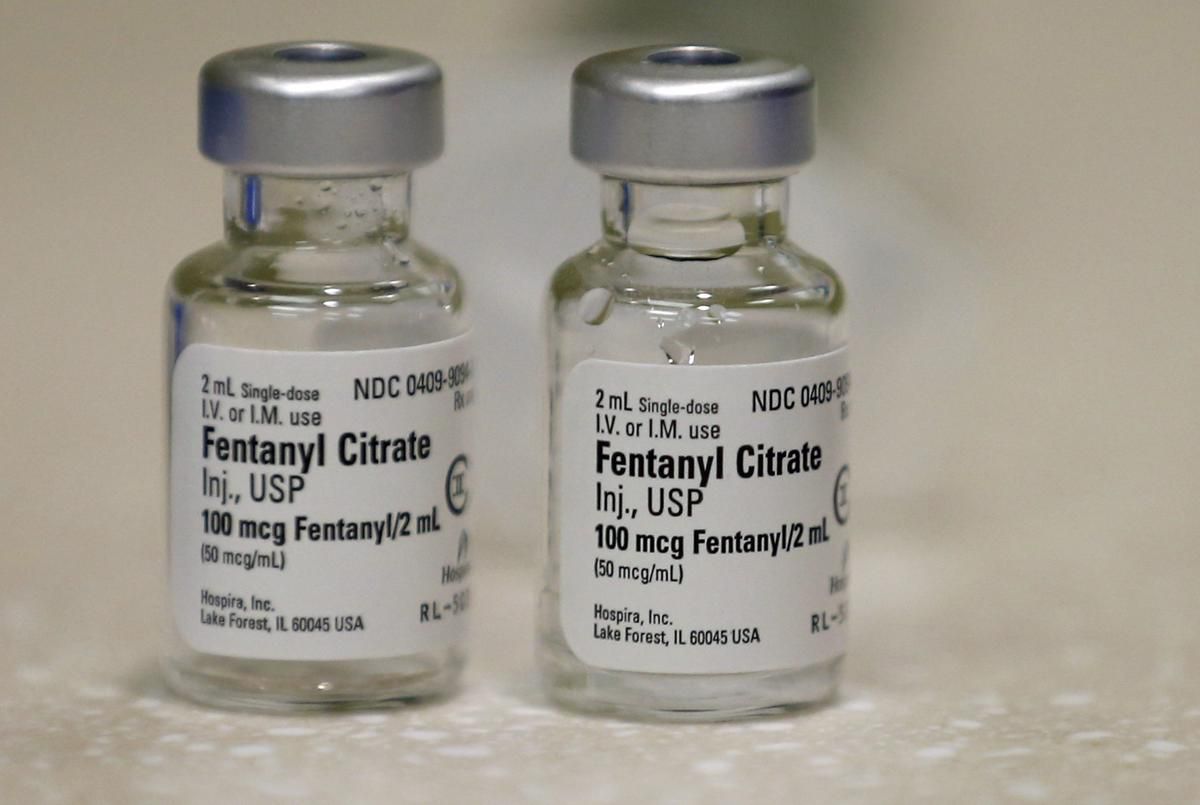

The drug is used in hospitals as a powerful anesthetic for surgery and is also prescribed to alleviate severe pain associated with terminal illnesses such as cancer. It can be given in the form of tablets, skin patches or injections.

It is especially dangerous because it is 100 times more powerful than oral morphine and 20 to 40 times more potent than heroin, making the risk of overdose much higher, according to Health Canada.

An amount the size of a few grains of salt can be enough to kill an adult, according to Health Canada.

Remifentanil is about twice as strong as fentanyl; sufentenil is five to 10 times as potent.

Much of the missing fentanyl detailed in the federal records may simply be wastage — for example, a container is discarded without being empty. But theft is a reality hospitals must confront, said Debra Merrill, president of the Ontario Branch of the Canadian Association of Hospital Pharmacists.

She added she’s not aware of any studies that would put the statistics obtained by the Star in context.

American expert Thomas A. Smith said it’s tough to put the Canadian numbers in context. In the U.S., theft of hospital drugs is common but rarely discussed openly, he said. Most of that theft is by staff members with substance problems, he said.

“Estimates are that 10 to 15 per cent of health care workers misuse alcohol or drugs at some point in their careers, which is similar to the general population,” said Smith, president of Heathcare Security Consultants Inc. and who has testified as an expert witness in U.S. court cases involving hospital security.

The worst form of that misuse, he said, is diversion by substitution, in which a staff worker steals a drug meant for a patient, then gives that patient something else. “This is a dangerous criminal situation requiring swift action and should result in criminal charges.”

According to the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists’ guidelines for preventing diversion, most thefts of drugs in hospitals are for the personal use of staff.

“Although it may be true that increased contamination of street drugs has increased the demand for ‘safer’ pharmaceutical-grade opioids diverted from the health system, most health professionals who divert are not doing so for purposes of trafficking,” the guidelines say. “Rather, in most cases, the diverter is suffering from substance use disorder.”

Merrill, who’s also director of the pharmacy program at Royal Victoria Regional Health Centre in Barrie, noted that her hospital alone uses 1,000 millilitres of fentanyl a day.

“We’re just one small hospital,” she said, adding that hospitals have systems to closely track the drug. Those systems monitor employees’ use of the drug, she said.

Read More:

Health Canada introduced a more precise system for reporting missing fentanyl in January 2019, said Samantha Yau, president-elect of the Canadian Society of Hospital Pharmacists, Ontario branch.

This should result in fewer cases of unexplained loss, she said.

Some fentanyl enters the Canadian drug market through theft of pharmaceutical fentanyl products, according to Health Canada. The drug also reaches the street via illegal importation from other countries and illegal production inside Canada.

The Public Health Agency of Canada recently reported that more than 10,300 Canadians lost their lives to opioids like fentanyl between January 2016 and September 2018. The highest concentration of deaths was in British Columbia, Alberta and Ontario, according to the government agency. Ninety-three per cent of those cases between January 2018 and September 2018 were accidental overdoses.

Asked what should be done to prevent medications going missing, U.S. expert Smith suggested strong auditing, security practices and awareness programs.

Merrill said hospitals are working to reduce theft, including installing sophisticated vaults for storing drugs, with live camera feeds in the storage room and in hallways to ensure the drugs are held “in restricted areas inaccessible to the public,” Merrill said.

“Alarm systems are mandatory,” Merrill said. “Narcotics counts are conducted multiple times a day and at least two people must sign off on all transactions.”

There are also advances in software to detect missing narcotics, she said.

“All discrepancies are to be resolved before the individuals involved in the discrepancies can leave their shift,” Merrill said.

That said, Merrill said there is potential for theft through things like shortchanging medication to patients, a crime that wouldn’t even end up on the missing fentanyl statistics.

“Is there potential?” she asked. “Yes. There is always a potential.”

Peter Edwards is a Toronto-based reporter primarily covering crime. Reach him by email at pedwards@thestar.ca

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments