03 Jul Coroner overdose data show fentanyl still driving fatalities in Louisville –

Local government data show that while Louisville EMS overdose runs and naloxone administrations have fallen so far this year to the lowest levels since 2015, fatal overdoses ticked up in the first quarter of 2019 — driven once again by the powerful opioid fentanyl, which was present in the toxicology report of 70% of victims.

Data from the Jefferson County Coroner’s office shows that while fatal accidental overdoses fell by 25% last year from the record high of nearly 400 in 2017, there were 94 deaths in the first three months of 2019, a notable increase from the monthly average of 25 in the previous year.

While the monthly total of fatal overdoses fell dramatically in the second half of 2018 to lows not seen since 2015 — before fentanyl emerged in the illicit drug market — the number of deaths ticked back up to 34 in January, the highest monthly total since the 40 recorded in August of 2017. After dipping to 23 fatal overdoses in February, the total rose even higher to 37 in March.

As was the case in each of the past two years, the coroner data shows that fentanyl was the main driver of overdose deaths in the first quarter, as the opioid was involved in 66 of the 94 fatalities. Fentanyl emerged in late 2015 and was involved in only 11% of fatal overdoses that year, but quickly rose to 43% in 2016, 64% in 2017 and 69% last year.

The 28 fentanyl-related fatal overdoses recorded in March was the highest monthly total since 33 in February of 2017, which was the peak of Louisville’s opioid epidemic.

Over 86% of the fatal overdoses in the first quarter of this year involved some type of opioid, consistent with the percentages found in coroner data from each of the past two years. Nearly a third of fatal overdoses involved methamphetamine, with 77% of those individuals also having an opioid in their system, mostly fentanyl.

Just over 10% of overdose victims in the first quarter of 2019 resided outside of Jefferson County — mostly in Southern Indiana or nearby Kentucky counties to the south — which is a percentage consistent with previous years.

While the fatality statistics so far in 2019 are disappointing after the optimism from the steep decline in late 2018, data from Louisville EMS shows that overall overdose runs and patients treated for an opioid overdose are actually still declining through the first five months of this year.

The 2,591 overdose calls to 911 from January through May in Louisville are the lowest total from this five-month period since 2015, despite rising to 633 in May. Likewise, the 842 patients who received a dose of naloxone on those runs — the drug used to revive victims of an opioid overdose — is also the lowest total since 2015.

Lori Caloia, medical director for the Metro Department of Public Health and Wellness, told Insider Louisville in an interview that while the coroner statistics from the first quarter of 2019 were concerning, it was too short of a time frame to suggest that last year’s progress in the fight against the opioid epidemic is starting to reverse itself — especially with other overdose metrics continuing to trend downward.

“I feel like we have made progress in meeting a lot of the goals that we’ve tried to accomplish with our substance use disorder plan, but I think we still have a lot of work to do,” said Caloia. “I feel fortunate that we’re in Jefferson County and have some of the resources that we do and some of the support that we do. I feel like we’re fighting less of an uphill battle and more of a unified fight against substance use disorder. But definitely, we still have a lot of work to do.”

In addition to the decrease in EMS overdose runs and administrations of naloxone over the first five months of the year, Caloia pointed to the progress that has been made in making naloxone more accessible. Whereas the health department’s syringe exchanges used to only give clients a card that would allow them to get naloxone at a pharmacy, they started distributing naloxone directly at those exchanges in March.

“We have gone from what in my mind did not seem like a very efficient program … you had to get to the pharmacy, you had to request that and that was just one more barrier that I felt was limiting people’s access to getting naloxone,” said Caloia. “So we have been able to actually distribute naloxone on site to our clients here, both at our syringe exchanges and at our MORE Center, to try to get more naloxone on the street.”

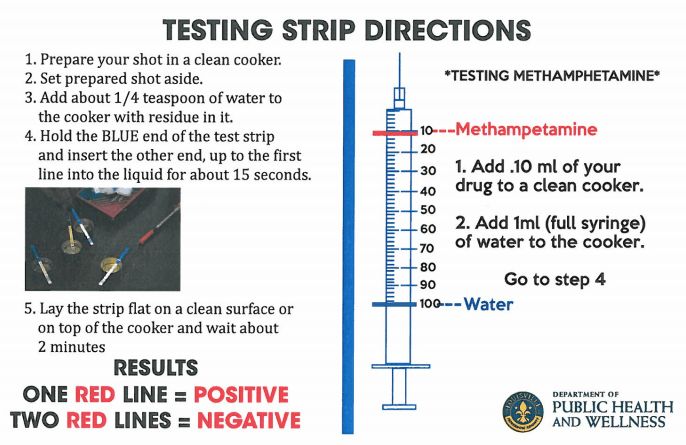

The large proportion of fentanyl-related overdose deaths remains a “major concern” to Caloia, though she expressed optimism because of the health department’s new policy to distribute free fentanyl-testing strips to syringe exchange clients, which allow them to test whether drugs like meth or heroin have been laced or cut with the far more powerful opioid that can be lethal in even small doses.

“Our experience in our syringe exchange is that people will alter their behavior around drug use if they know that they are going to be using something that contains fentanyl,” said Caloia. “We are asking them about these behaviors, and it does change the decisions that they’re making.”

Caloia also said that the state’s decision to expand Medicaid coverage to medication-assisted treatment using methadone could be a huge boost to the department’s effort to fight opioid use disorder and break down barriers to access.

“Even in our MORE Center, where we provide methadone treatment, we had a fee schedule… we didn’t have a mechanism by which we could provide the medication, bill insurance and make it more affordable for people,” said Caloia. “We would lose a lot of clients, folks that might do well in the program, purely out of financial reasons. So I think we’ll see that financial barrier decreased substantially for people.”

Besides this Medicaid change, Caloia said that she has seen the city making less progress on the front of getting people with substance use disorder into evidence-based treatment and medication-assisted treatment, where barriers still remain.

One such barrier is the state’s Medicaid requirement that buprenorphine prescriptions — often known by the brand name Suboxone — must go through a prior authorization process, which often ends in a denial.

Caloia added that many providers and recovery specialists still remain resistant to medication-assisted treatment using methadone and buprenorphine because they are themselves opioids that have the potential to be diverted — and can be difficult for patients to deal with — even though peer-reviewed research has shown this to be an effective evidence-based treatment.

“The most effective that tends to retain people in treatment longest are going to be methadone and buprenorphine,” said Caloia. “The longer we keep people in treatment, the more likely they are to stay in treatment, the more likely they are not to overdose, the more likely they are to continue on the road of recovery.”

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments