08 May Fentanyl Facts and Fiction: A Safety Guide for First Responders

Fentanyl, a potent synthetic opioid, was first synthesized in December 1960 by Dr. Paul Jansen in Belgium. It was developed as an IV analgesic and its first clinical use was recorded in 1963. Fentanyl was brought to the United States in 1968 and today, is one of the most frequently used intraoperative analgesics across the world.1

Facts About Fentanyl

Fentanyl is available in a variety of forms including transdermal patches, as well as nasal, buccal, sublingual and transmucosal preparations used to treat a variety of acute, chronic, cancerous and palliative pain conditions.

In prehospital emergency care, fentanyl is now a common medication for the relief of severe pain associated with acute injuries and illnesses. Its popularity stems from its minimal cardiovascular effects, lack of increases in plasma histamine, rapid onset of action, relatively short half-life, and low cost resulting from its ease to synthesize and produce.

Fentanyl functions in the same manner as other opioids, binding with neurochemical transmitters in the central nervous system, providing analgesia and sedation. It blocks the transmission of pain signals and activates the parasympathetic nervous system.

Fentanyl also binds to the same brain receptors as naturally produced endorphins such as dopamine, serotonin and oxytocin, causing feelings of euphoria and pleasure at levels similar to those experienced during sexual intercourse. With repeated exposures, the human body quickly adapts to this increased endorphin production and when endorphin levels drop, feelings of depression, pain and physical craving occur. These neurochemical changes are a primary physiological agent of addiction.

In the respiratory system, fentanyl causes decreased respirations, cough suppression and smooth muscle relaxation. In the gastric system, it decreases oral secretions, slows gastric motility and causes constipation.

Signs and symptoms of fentanyl ingestion, as well as opioid toxicity and overdose in general, include respiratory depression and apnea, altered mental status, confusion, hypoxia, diaphoresis, miosis (i.e., constricted pupils) and slurred speech.

Fentanyl and its analogs, such as acetyl, butyryl or furanyl fentanyl, are relatively simple and cheap to produce. They’re also incredibly potent at lower concentrations compared to other opioids such as oxycodone (Oxycontin), morphine and heroin. Consequently, there have been significant increases in its presence in the illicit drug supply throughout the United States. Much of this fentanyl is manufactured in China and smuggled by Mexican drug cartels, along the same routes used to traffic heroin. In some cases, it’s also now being manufactured in clandestine drug labs in the U.S. In 2018, DEA agents raided what they thought was a methamphetamine lab in a western Pennsylvania hotel room; it turned out that the room’s occupant had been trying to make fentanyl.

Fentanyl has been found to be packaged and distributed as a standalone product. More often, however, it is used as a cutting agent to increase the profitability of heroin and other illicit drugs. According to the DEA in Philadelphia, a kilogram of heroin sells for $50,000 to $80,000, and a drug trafficker can make about $500,000 in profit. A kilogram of fentanyl sells for $53,000 to $55,000, is 50 times stronger than heroin, and can render profits in excess of $5 million.2 The addition of fentanyl to heroin as well as other illicit drugs is a primary cause of the recent explosion of opioid related deaths that peaked in 2017, when approximately 72,000 Americans died.

Fentanyl isn’t just being mixed with opioids. In some tests, a majority of all illicit pills and powder, including cocaine, crack, methamphetamine, PCP and ecstasy (i.e., MDMA) now contain fentanyl or one of its analogues. A November 2018 report in the New England Journal of Medicine describes a cluster of overdoses in Philadelphia where 18 patients who had not intentionally ingested opioids presented to medical facilities with apparent opioid overdose. All reported smoking what they believed to be crack cocaine. Four of the patients died and others experienced significant sequelae. All 18 cases occurred in a short period of time and in the same zip code indicating a point source. EMS providers must remain vigilant and be prepared to treat patients presenting with symptoms consistent with the opioid toxidrome who did not knowingly ingest opioids.

Fact or Fiction?

Over the course of the last few years, there have been numerous reports where police officers, firefighters, EMS providers and other emergency responders have described acute illnesses after being in close proximity to illicit powder believed to contain fentanyl. There’s a growing concern that merely being near fentanyl can lead to passive exposure, presenting a life-threatening hazard.

In many of these case reports, the responders believe that inert powdered product is being aerosolized and inhaled or transdermally absorbed through the skin, even when little to no visible skin contact has occurred. The victims complain of a variety of nonspecific symptoms including dizziness, anxiety, fatigue, dyspnea, nausea, vomiting and syncope. In some cases, they self-administer naloxone (Narcan). In others, they’re treated and transported to the hospital by EMS. All of the supposed victims recovered quickly without any significant complications.

In May 2017, a police officer in Liverpool Ohio reported brushing a white powder off of his uniform after a traffic stop. The officer reported that he immediately began feeling lightheaded and dizzy and then experienced syncope. He was rushed to the hospital where he was treated and made a full recovery.

In July 2017, a police officer in Menasha Wisconsin, reported feeling lethargic and groggy, felt a tingling sensation in his hands and feet, and then nearly passed out hours after responding to a fatal overdose at a residence. According to local news outlets the officer believed that being at the scene of the death led to passive exposure to fentanyl. Multiple doses of naloxone were administered, and the officer was transported to the hospital where he made a full recovery.

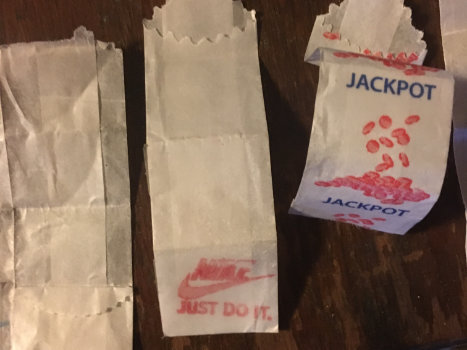

Figure 2: A portion of an advertisement used to market gloves to first responders

Growing Hysteria

Cases like this are becoming widespread and there’s a growing public hysteria. Some are seeking to profit from the perceived crisis, advertising personal protective equipment manufactured specifically to protect first responders from the supposed threat of passive exposure to fentanyl. This profiteering only serves to increase stigma as well as provide unsubstantiated validation to individual and organizational bias and fear.

An ad for a PPE product manufactured specifically to protect from the supposed threat of passive fentanyl exposure.

Photo courtesy Twitter/theschwarziee

To date, there’s been no toxicological evidence to support the conclusion that these individuals actually experienced opioid toxicity. There’s unanimous agreement among physicians and toxicologists that toxicity and overdose from passive exposure to fentanyl isn’t possible. If there was a real hazard, it stands to reason that the people who produce fentanyl, distribute it, or use it would suffer similar exposures. This is simply not happening.

Some of the victims may have suffered legitimate medical problems that coincidently occurred after the perceived exposure, while others appear to be suffering from psychosomatic symptoms related to fear and anxiety. The pervasive anxiety surrounding passive exposure to opioids is only serving to increase the stigma associated with people who use drugs.

This at-risk population already struggles to get the vital medical care needed for them to survive and recover, and this misconception is only serving to make access more difficult. There have been reported incidents of overdose patients not being provided appropriate medical care; hazardous materials response teams are being activated erroneously; or criminal charges being leveled against individuals based upon the belief that their actions endangered responders. This must stop. It’s our duty as healthcare professionals and patient advocates to ensure that all stakeholders receive the necessary education to dispel these myths and that clear, evidence-based safety guidelines are provided.

In December 2017, the American College of Medical Toxicology (ACMT) and the American Academy of Clinical Toxicology (AACT), the two preeminent organizations representing medical toxicologists across the country, published a joint position statement discussing occupational fentanyl and fentanyl analog exposure to emergency responders. In the document they stated unequivocally that the risk of clinically significant exposure to fentanyl and its analogs to emergency responders is extremely low.3

Additionally, the report states that the transdermal absorption of fentanyl powder is extremely unlikely to occur. It’s further noted that inert fentanyl powder isn’t aerosolized, and it would be exceptionally rare for drug droplets or particles to be suspended in the air.3

Safety Guidelines

Below are safety guidelines for operating at emergency scenes where suspected fentanyl powder is present:

1. Standard nitrile medical gloves and duty uniforms provide adequate dermal protection. If suspected fentanyl powder is found on skin or clothing, the dry powder should be brushed away and then the area should be cleansed with soap and water. Contact with intact skin or clothing isn’t considered a hazardous exposure.

2. Respiratory protection isn’t required for routine operations. In the extremely unlikely event that it’s suspected that drug droplets or particles are suspended in the air, standard disposable N95 masks will provide sufficient respiratory protection.

3. Naloxone should be readily available, and all responders should be trained in its use and administration. Naloxone should only be administered to individuals who present with objective signs of opioid toxicity such as altered mental status with hypoventilation, unconsciousness and respiratory depression. Naloxone isn’t indicated for individuals who experience vague sub-clinical symptoms like nausea, vomiting, fatigue, dyspnea, dizziness and anxiety.3 In the unlikely event that an exposure to fentanyl occurs, in the absence of extended hypoxia, there’s no long-term risk to responders.

Conclusion

Fentanyl has a multitude of necessary medical uses and its value to pain patients is significant. Unfortunately, despite the best efforts of law enforcement agencies, there’s no indication that its illicit production, distribution and use is going to be stopped.

The public hysteria and misconceptions about fentanyl can’t be allowed to jeopardize its legitimate use. Law enforcement officers, EMS providers, firefighters and other first responders must be properly trained to safely respond to incidents where illicit fentanyl is present without unnecessary anxiety. The guidelines presented here represent the best evidence currently available and can serve as a standard for all stakeholders.

The public at large looks to public safety professionals for guidance and iut’s imperative that we adopt recognized best practices to reduce their fear.

References

1. Stanley TH. The fentanyl story. J Pain. 2014;15(12):1215–1226.

2. Whelan A. (Oct. 24, 2018.) How fentanyl, the deadly synthetic opioid, took over Pennsylvania. The Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved May 7, 2019, from www.philly.com/philly/health/fentanyl-synthetic-opioid-drug-overdoses-philadelphia-pennsylvania-20181024.html.

3. Moss MJ, Warrick BJ, Nelson LS, et al. ACMT and AACT position statement: Preventing occupational fentanyl and fentanyl analog exposure to emergency responders. J Med Toxicology. 2017;13(4):347–351. doi:10.1007/s13181-017-0628-2 (Also accessible here.)

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments