23 Jun Fentanyl rising as killer in San Francisco — 57 dead in a year

Fentanyl, the synthetic painkiller that is up to 100 times more potent than morphine and has ravaged drug users on the East Coast, appears now to be fully embedded on San Francisco’s streets, surpassing prescription pills and heroin as the leading cause of opioid overdose deaths in the city.

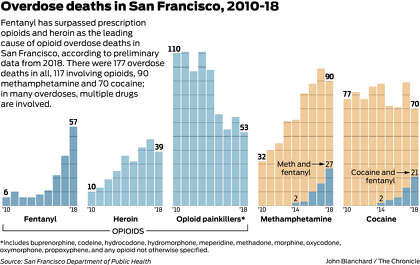

In 2010, just six overdose deaths in San Francisco were attributed to fentanyl. In 2018, that number hit 57. By comparison, 39 overdose deaths were attributed to heroin last year and 53 to prescription opioids like oxycodone and codeine.

Though the 2018 numbers from the city’s Public Health Department are preliminary and need to be confirmed, anecdotal reports from drug users and people working with them in the community back up the overdose stats.

Fentanyl hit the San Francisco market first as a powerful contaminant of other street drugs, leading people to overdose because they didn’t even know they were taking it. Now, in a dangerous trend, it’s replacing heroin and prescription pills as some users’ narcotic of choice.

“A couple of years ago we started seeing fentanyl powder popping up on the street and normalized as an additional opioid in San Francisco. And now it’s fairly established,” said Dr. Phillip Coffin, director of substance use research for the health department. “It’s not going away anytime soon.”

While precise numbers aren’t available, the trend in 2019 isn’t looking promising: In the first two weeks of June, 10 people suffered fatal opioid overdoses in the city — more than twice the usual number, and all from fentanyl. That prompted public health officials to warn that a particularly potent batch of the drug appeared to be circulating.

Fentanyl has been used to treat severe pain for decades, often administered to people recovering from surgery or suffering from cancer. But over the past 10 years it has become one of the main causes of addiction and overdose in the United States.

In 2010, about 14% of opioid-related overdose deaths across the country were attributed to fentanyl; by 2017, 59% were from fentanyl, according to the National Institute on Drug Abuse.

Until recently, though, fentanyl was largely an East Coast problem. It has circulated on the West Coast, including San Francisco, since the 1980s, but people rarely chose it over heroin. It wasn’t easily available and was used in such low levels that public health officials didn’t always track it.

Fentanyl’s first troubling forays into San Francisco caught public health and addiction experts by surprise.

In 2015, multiple overdose deaths were attributed to one batch of white powder that users hadn’t known contained fentanyl. A year later, multiple deaths were attributed to a single supply of Xanax tablets that contained fentanyl. Next it was found in crack cocaine, then in methamphetamine. The overdoses and deaths kept climbing.

Public health officials began spreading the word among users that fentanyl was “contaminating” the street drug market, said Dr. Barry Zevin, medical director of street medicine for the public health department.

For the most part, no one was trying to buy fentanyl. Instead, they were accidentally using it when it was cut with their preferred drug, usually heroin or methamphetamine. And that’s still a problem. Among the 90 overdose deaths attributed to methamphetamine last year, nearly a third also involved fentanyl.

Zevin said that every now and then he’d hear from users who preferred fentanyl over other street drugs — usually people who had relocated to San Francisco from the East Coast. But that was rare.

Things started drastically changing last year, he said. Increasingly, the users he worked with said they were actively seeking fentanyl.

The reasons are fairly simple. Smaller amounts of the drug are needed to get high or to stave off withdrawal symptoms, so fentanyl can be cheaper than heroin. Also, many users say that smoking fentanyl gets them just as high as injecting heroin, and they prefer to smoke because it’s safer than using needles.

Fentanyl is more available now than it was a year or two ago. It’s basic economics: The more people are buying the drug, the more people are selling it.

“Fentanyl has just flooded the market,” said Roger Boyd, 35, who prefers heroin but said he has been using fentanyl more often over the past year simply because it’s there. “I really don’t love the stuff. A lot of people are overdosing on it. But I switched because a lot of my friends switched.”

What worries Boyd and other users is that fentanyl’s potency makes it tricky to get the dosing just right, which in turn makes it easy to overdose.

In medical settings, pharmacists with sensitive equipment weigh dosages almost too small to see with the naked eye and then parse them out among measured saline solutions. Sometimes fentanyl is absorbed through patches applied to the skin, or people consume it by sucking on hard candies dosed with the drug. Both techniques allow it to be taken slowly, so the risk of overdose is very low.

Fentanyl sold on the street typically comes in small plastic baggies that hold about 100 milligrams of soft white powder and cost about $20. The drug is mixed with something else: crushed antianxiety pills, the anesthetic lidocaine, sometimes just sugar or a sugar substitute.

Getting the fentanyl to mix thoroughly with the other powders isn’t easy. It can clump up, so that one plastic baggie may be 50% fentanyl and another might be less than 5% — or have none at all. And there’s no easy way for users to test for potency.

“It’s just this gamble — is it going to be too good this time, or not good enough?” Boyd said.

On a recent morning, a block and a half from the crowded farmers’ market at United Nations Plaza, Boyd and some friends were sitting under a construction awning, taking turns smoking fentanyl off a strip of tin foil that they heated with a lighter.

They never use it alone, Boyd said, because it’s so easy to overdose. Someone needs to stay alert enough to provide naloxone — the overdose reversal drug, often sold under the brand name Narcan — or call for help if one of them stops breathing.

“We don’t want any of our homies to die,” said Sha, 30, who was sitting with Boyd and did not want to give his last name.

Sha said he had been using fentanyl since he was a teenager, when he’d steal his grandmother’s painkillers, which were prescribed as lollipops so patients would consume them slowly.

He kept using the drug as an adult, but said he was concerned to see fentanyl becoming much more common on the street. Many of his friends, who are used to heroin or other drugs, don’t understand how much stronger fentanyl can be and how easy it is to overdose. They don’t know the proper precautions to take, like starting with small doses and never using alone.

Community experts in addiction and harm reduction said they have similar worries. They noted that the city has a lot of good strategies for helping drug users stay safe and avoid overdoses. Widespread distribution of naloxone has been especially effective.

But with fentanyl, “There’s less room for error,” Coffin said. It can take half an hour or longer to die from a heroin overdose without treatment. With fentanyl, people can die in just five minutes, and on an amount as small as a grain of sand.

Of the 10 people who overdosed this month, nine were alone when they died, officials said.

About a year ago, San Francisco nonprofit groups that support people who use drugs began establishing a “five-minute rule” on public restrooms: Staffers check on them every five minutes for possible overdoses, said Paul Harkin, director of harm reduction programs at Glide.

“The last two years or so, fentanyl has really started to come in bulk. We’ve actually had dealers tell us they’re about to get a bunch of fentanyl in, so we’d better stock up on the Narcan,” Harkin said. “Fentanyl is here to stay. You can get it all over the city.”

Erin Allday is a San Francisco Chronicle staff writer. Email: eallday@sfchronicle.com Twitter: @erinallday

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments