18 Dec Inside America’s other opioid epidemic

-

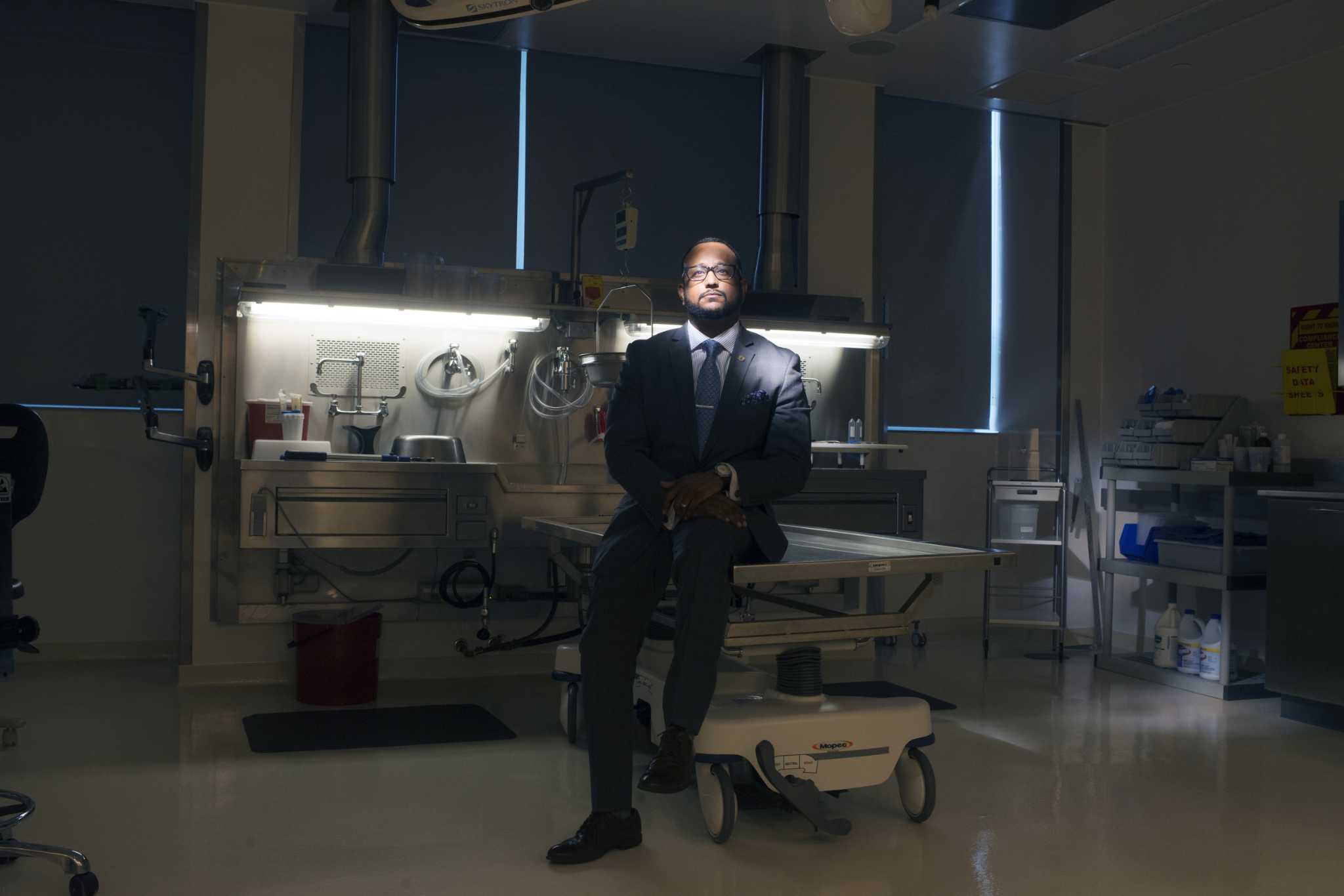

Roger Mitchell Jr. took over the District of Columbia’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in the winter of 2014, is photographed at the Department of Forensic Sciences in Washington, D.C. on April 06, 2016.

Roger Mitchell Jr. took over the District of Columbia’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in the winter of 2014, is photographed at the Department of Forensic Sciences in Washington, D.C. on April 06, 2016.

Photo: Washington Post Photo By Marvin Joseph

Roger Mitchell Jr. took over the District of Columbia’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in the winter of 2014, is photographed at the Department of Forensic Sciences in Washington, D.C. on April 06, 2016.

Roger Mitchell Jr. took over the District of Columbia’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in the winter of 2014, is photographed at the Department of Forensic Sciences in Washington, D.C. on April 06, 2016.

Photo: Washington Post Photo By Marvin Joseph

WASHINGTON – Spoon, whose product could be trusted, wasn’t answering his phone. So just after 9 a.m. on a fetid August morning, Sam Rogers had trekked to a corner two miles east of the U.S. Capitol on Pennsylvania Avenue, hoping to find heroin that wouldn’t kill him.

Now Rogers, 53, was back in his bedroom at the hot, dark house. Sitting in a worn swivel chair, he cued a Rob Thomas song on his cellphone and bent over his cooker and syringe. The heroin – a tan powder sold for $10 a bag – simmered into a cloudy liquid with the amber hue of ginger ale.

Palliative or poison: He would know soon enough.

“Come on,” Rogers murmured, sliding a needle into his outer forearm between knots of scar tissue. A pink plume of blood rose in the barrel of the syringe. “There you go.”

In the halls of Congress, a short bus ride away, medical professionals and bereaved families have warned for years of the damage caused by opioids to America’s predominantly white small towns and suburbs.

Almost entirely omitted from their message has been one of the drug epidemic’s deadliest subplots: The experience of older African-Americans like Rogers, for whom habits honed over decades of addiction are no longer safe.

Heroin laced with the powerful synthetic opioid fentanyl has killed thousands of such drug users in the past several years, driving a largely overlooked urban public-health crisis. Since 2014, the national rate of fatal drug overdoses has increased more than twice as fast among African-Americans as among whites, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In this new explosion of deaths, the nation’s capital is ground zero. The District of Columbia saw 279 people die of opioid overdoses last year, a figure that surpassed the city’s homicides and was greater than three times the number of opioid deaths in 2014. More than 70 percent of cases involved fentanyl or its analogues, according to the District’s chief medical examiner, and more than 80 percent of victims were black.

Rogers knew the danger as well as anyone. He had used heroin for three decades, but it was in the past two years that he had nearly died of overdoses – twice – and twice been rescued by his girlfriend and fellow user, 59-year-old Renee Howell.

Every fix had become a life-or-death gamble, although the outside world was paying little attention to how the die fell.

Rogers depressed the plunger on his syringe. It was the moment of truth that came with every new bag: The 300 microliters of heroin now entering his bloodstream could easily kill him if it had been “stepped on,” or cut, with fentanyl.

His dark eyes scanned the overcast sky beyond his bedroom balcony.

Sweat streamed down his face.

He sank into his seat and grinned.

– – –

Big Pharma and pill mills. Hillbilly Heroin, prescription drug monitoring programs and gaunt teenagers moving from Percocet to the needle. These are the familiar themes and characters of the story America has told itself about its opioid epidemic, a story set in the mobile-home parks and suburban subdivisions of Appalachia, New England and the Midwest.

It is a story that is increasingly outdated and incomplete.

For several years, the opioid scourge has been moving into cities – and claiming the lives of African-Americans at unprecedented rates. Unlike the white overdose victims who have dominated national debate, the epidemic’s new casualties are seldom young and were not first hooked by doctors prescribing pain pills.

Instead, they are the long-term drug users who have endured the older, slow-burning opioid epidemic that began with heroin’s spread through American cities in the Vietnam War era. Many, like Rogers and Howell, had developed a semblance of functional addiction, getting by with menial jobs on factory floors and construction sites.

Until they began dying.

Between 2005 and 2014, a period when abuse of prescription opiates peaked and heroin use began surging in rural and suburban areas, the national rate of deadly drug overdoses among African-Americans climbed by 12.1 percent, far below the 53.7 percent increase for whites over the same period, according to data from the CDC. Between 2014 and 2017, the fatal overdose rate among African-Americans shot up by 94.1 percent – more than double the 44.6 percent increase for whites.

The resulting deaths have disproportionately hit cities and other densely populated areas. About 7 in 10 African-Americans who died of a drug overdose in 2017 lived in counties classified as heavily urban by the National Center for Health Statistics, compared with 3 in 10 whites.

America’s opioid epidemic has changed. And what changed it was fentanyl.

A molecule shaped like a cocked handgun, fentanyl was synthesized by the Belgian doctor and chemist Paul Janssen in 1960. Its potency is as much as 100 times that of morphine. For a half-century it was used as a surgical anesthetic and treatment for patients in chronic, intense pain.

But by 2014, fentanyl was being manufactured in China and imported to Mexico, where it was mixed into the powder heroin distributed east of the Mississippi River. Inexpensive and easy to produce, compared with the opium poppy, fentanyl arrived at the right moment for drug distributors seeking to stretch their inventory for the U.S. market. But it came with a drawback: Its extreme potency makes even slight miscalculations deadly when it is added to heroin.

Fentanyl has decimated opioid users of every demographic. But its effects are especially pronounced among older African-Americans caught off guard by the sudden lethality of heroin they had learned to use with relative safety. Those veteran, urban users – who typically dread and seek to avoid fentanyl – are still left out of policy discussions about the opioid epidemic, said Daniel Ciccarone, a heroin expert and professor at the University of California at San Francisco.

“The face of the epidemic is white,” Ciccarone said. “That’s what’s reported in the papers. That’s what’s discussed in the congressional meetings. It is not yet on anyone’s radar that it’s converting in the cities to a majority-black epidemic.”

Kathie Kane-Willis of the Chicago Urban League said black heroin users have also been excluded from changing national attitudes toward drug abuse.

For African-Americans, she said, government intervention in the opioid epidemic remains synonymous with harsh law enforcement policies pioneered in the 1970s and 1980s. By contrast, white users today are often viewed as victims – of drug companies, of unscrupulous doctors, of addiction as a physically based disease – and targeted with public-health campaigns to prevent overdoses and help them enter treatment.

“We’ve been focusing so exclusively on the white community that we haven’t thought about how to approach the African-American community,” Kane-Willis said. “And the result is unprecedented, extremely high rates of death.”

Those deaths can be seen in Philadelphia, where officials have labeled a fentanyl-fueled rise in overdoses the city’s foremost public-health threat.

They’re evident in Baltimore, where fentanyl has devastated neighborhoods that seemingly could not suffer further depredations from the drug trade.

And in the District of Columbia, where – in the shadow of a federal government that has spent billions in a bipartisan push to combat opioid addiction – many of the opioid epidemic’s victims are hiding in plain sight.

– – –

They had come together a decade ago in Baltimore, Maryland, a pair that looked more like the couples buying crab cakes inside the huge Lexington Market than the panhandlers nodding off outside. Rogers was an extrovert with broad shoulders and a high-pitched laugh. Howell was well-read and demure, still bearing the traces of her middle-class upbringing in northwest Baltimore.

Their generation was born as heroin was seeping out of jazz clubs and writers’ salons into the urban neighborhoods it would gradually destroy. The corners of West Baltimore that Rogers and Howell began to frequent in their youth were minor scenes in a story that stretched from Myanmar to the Andes, a tale interwoven in the United States with racial divisions and the economic decline of formerly booming cities. But they didn’t blame any of those things for their addiction.

“Both of us grew up in decent families and households,” Howell said. “I don’t have no excuse, no molestation or anything. I just wanted to try it.”

And try it they did, through needle and nose, in discos and in dark bedrooms lit by guttering candle flames. Rogers began trying it in his 20s and lost a succession of blue-collar jobs – at fast-food joints, a plastics manufacturer, a frozen-food plant – before he eventually did four years in prison on drug charges. Howell began trying it more than 30 years ago, her only clean time since then when she was pregnant or behind bars on the kinds of charges long-term addiction often entails, she said, including nine months in prison for theft.

As they grew older, they learned the lessons heroin inexorably imparts on those who use it long enough: how necessity replaces pleasure, and illicit thrills give way to a daily ritual of morning shivers and nausea. Sometimes, Howell said, she would sit in her parked car and watch strangers walk by, imagining how they passed their days, trying to remember what life was like outside the grip of addiction. She had been raised in a Baptist family and believed God intended something better for her.

So when Rogers learned in 2013 of a chance to rent space in a two-story brick home in Southeast Washington, they seized it, hoping that escape from Baltimore’s drug scene would give them a shot at getting clean. The couple enrolled in methadone treatment, and for a time they stopped using heroin completely.

It didn’t last.

Rogers left treatment after a year, and within a few years both were using again. But something had changed.

There was talk of a new poison in the dope supply. Reprising an old conspiracy theory about crack cocaine, some said the federal government had introduced it to thin the black population. Others said it was Joaquin “El Chapo” Guzman’s revenge for the U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s role in his 2014 arrest. People were “falling out” – overdosing – fast and hard, in a way no hard slap or splash of cold water could reverse.

Soon Rogers was one of them.

It hit him in their bedroom on a summer day in 2016: an unfamiliar, etherizing wave. Howell, who had snorted a smaller amount of the same dope Rogers injected, felt lightheaded but remained conscious to see him slump to the floor. Thinking he was clowning, she laughed. When he wouldn’t wake up, she panicked.

That moment had been a crucible for Howell. She had spent enough time in jail to know she never wanted to go back, and was afraid of what might happen if she called 911, inviting paramedics and police to what was technically a crime scene. But in those seconds when Rogers sprawled unresponsive at the foot of their bed, it wasn’t fear for herself that won out.

It wasn’t easy to draw a line between their love for each other and their love of heroin. At times Howell wondered whether they would have to separate to get clean. But she knew she couldn’t watch Rogers – who cooked her fried-shrimp dinners, who fed the cats she cherished without being asked, whose stubbornness and hot temper belied a resolve that was sometimes the only thing carrying them through their worst days – die on the floor.

“It’s him and I against the world,” she later explained.

Howell called 911. When the paramedics arrived, she showed them the syringe. And after they revived Rogers with the overdose antidote naloxone, she bought more of the medicine herself from a black-market salesman near her methadone clinic.

A month later she found Rogers on the kitchen floor, and used it.

Some might have expected them, after two brushes with death, to give up heroin. But not anyone who understood the drug’s euphoric release. It was a feeling Howell described as “taking a hundred coats off,” whose pleasure – while much diminished since the early days of their addiction – was still powerful enough to obscure the uglier details of their lives.

At an age when others contemplated retirement, they were piecing together rent and drug money from Rogers’s disability checks for his bad back, Howell’s wages at a cleaning service and the occasional sale of diapers and T-shirts that a friend stole from big-box stores.

As the summer of 2018 ended, their home of five years was being sold out from under them, and the power had been cut. Homelessness terrified them – they had never considered themselves that kind of drug user – but even in Southeast Washington one-bedroom apartments were renting for more than $1,000 a month.

When Spoon, the couple’s preferred dealer, dropped out of touch in early August, Rogers chose to take his chances with a lower-end vendor. He and Howell knew that switching suppliers was dangerous in the era of fentanyl. But for what heroin gave them, and despite all it took from them, this was a risk they were willing to take.

“You might wake up on the floor, wake up in the hospital or not wake up at all. That’s the chips that I’m playing with,” Rogers said. “And that’s all I have to say about that.”

– – –

Roger Mitchell Jr. took over the District’s Office of the Chief Medical Examiner in the winter of 2014. Mitchell – a bow-tie-wearing forensic pathologist who moonlights as a Baptist minister – had his hands full in his new job as he steered the lab toward its first full accreditation.

But several months into his tenure, he was briefly distracted from the slog of reforming his agency by an abrupt uptick in heroin deaths. In July 2014, there were 13 fatal overdoses. Back then no one knew what was coming, and that seemed like a lot.

“Whoa, whoa, whoa,” Mitchell recalled saying to his staff. “That’s, like, one every other day, right? What’s going on?”

Opioid overdoses continued to climb slowly through early 2016 – and then lurched decisively upward. March 2016: 20 deaths. May 2016: 28 deaths. November 2016: 37 deaths. Between Nov. 1, 2016 and June 1, 2017, someone was dying from an opioid overdose, on average, every day in the nation’s capital.

Mitchell had chosen a profession steeped in death. But the deaths of drug users had special meaning for him. The grandson of one of Atlantic City’s first black physicians, he was a child when he watched his father, a New Jersey business owner, become addicted to crack cocaine.

“I grew up knowing that substance-use disorder could happen to good families,” he said.

Mitchell’s father eventually got clean. The men and women whose bodies were now rolling into the medical examiner’s lab three blocks south of the Mall were not so lucky. Many of the victims were those known on the street as “old heads”: black heroin users in their 50s and 60s. Most were testing positive for fentanyl.

Even in a country where opioids are killing people at unprecedented rates, the District stood out. Between 2014 and 2017, the city’s rate of fatal drug overdoses rose by 209.9 percent – an increase higher than that in any state and the ninth-highest among all U.S. counties, CDC data show. (The agency does not track overdoses by city.)

Like much else in the capital city, it was a problem whose effects were wildly uneven across race and class. The District of Columbia’s rate of deadly drug overdoses among African-Americans was 74.6 per 100,000 in 2017, more than seven times the rate of the city’s white residents.

The District of Columia was in the midst of a full-fledged public-health crisis. But the news didn’t seem to have reached city hall, where elected officials had other priorities. As overdose deaths began to hit alarming levels in 2016, the city’s left-leaning lawmakers advanced a number of laws – a minimum-wage increase, generous parental leave benefits – that they said would shrink the disparities between rich and poor, black and white. Bold initiatives to address the opioid epidemic, concentrated in the black neighborhoods of Southeast and Northeast Washington, weren’t on the agenda.

Looking out the window as she rode the bus to church on a Sunday morning in mid-August, Howell could see what most of those in power did not: all the people who might fall out next.

She understood how little sympathy those men and women evoked, and how little they sometimes deserved. But she also couldn’t help noticing that they seemed to live under a different standard than a newer, whiter generation of opioid users.

Howell, Rogers and others like them had gotten the War on Drugs. Today’s users, many of them in small towns and suburbs, were getting billions of federal dollars for treatment programs. President Donald Trump would soon visit a hospital in Ohio to call attention to the opioid epidemic. But the politicians never seemed to show up on Good Hope Road.

Howell did not discuss such matters with her fellow parishioners at Good Hope Church, a Pentecostal congregation that meets in a multipurpose room furnished with folding metal chairs in southeast Washington. She told them her days of drug use were behind her, and she tried to have faith that God would one day make that lie the truth.

“Lord, it is hot, ain’t it,” said Eunice Winchester, 72, as she drove Howell home after the service in her two-door Chrysler.

Howell lit a cigarette and stared out the window. The Chrysler approached Barry Farm, a 75-year-old public housing project where sirens periodically blare from ambulances called to revive overdose victims.

“There’s so many sad, sad things around here,” Howell said. “You look at some of these people, they don’t got nobody.”

When she spoke, Winchester kept her eyes on the road.

“Some of them don’t want nobody,” she said.

– – –

On a rainy Saturday night in early September, Howell sat alone on the edge of her bed, eating Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups and smoking Newports. The French slasher DVD she was trying to watch, “High Tension,” kept stuttering and freezing on an image of white venetian blinds spattered with blood.

Most of their possessions were in moving boxes, though some daily necessities and decorations had not yet been packed. There was a package of V-neck tees they had been unable to sell. (“No one in the hood wears V-necks,” Howell lamented.) A print of “The Ballet Rehearsal on Stage” – Degas’s eerie depiction of exhausted ballerinas dancing before an empty theater, a gift from Howell’s aunt – hung on the bedroom wall.

She and Rogers had caught some lucky breaks. Earlier that week they had signed a lease for a new apartment around the corner, and as they waited to move out, a Realtor had restored the power at the house so that a renovation crew could begin work.

But money was more tight than usual – the new rent was $1,275 a month – and in the absence of steady drug funds Rogers was resorting to riskier means of securing product. He was volunteering more often to test a new package’s quality for drug distributors. Tonight he was out playing chauffeur, using a borrowed car to drive a dealer to a club.

Howell hated these absences. She dreaded what might happen if Rogers shot up without her, among people who didn’t care enough to try to bring him back if he fell out.

She cracked open a package of acrylic nails and glanced at her phone. Almost 9 p.m.

If he wasn’t back by the time she had finished, she would call.

Howell didn’t know it, but the District of Columbia would soon be receiving what amounted to good news in the fourth year of its opioid crisis. Fatal overdoses appeared to be slowing.

A November report from the chief medical examiner would identify 153 opioid deaths in the first nine months of the year. If that trend held, the 2018 body count, while still more than double pre-fentanyl levels, would be the lowest the city had seen in three years.

Medical providers and public-health officials can’t explain the decline, which is also being witnessed in other cities and states. Some speculate that halting efforts by the District’s public officials to warn users about tainted heroin and to make more naloxone available are having an effect. A grimmer hypothesis holds that there are only so many of the aging African-American users hit hardest by the epidemic in the District, and that fentanyl has already killed most of them.

Howell sometimes thought about leaving Rogers to get clean. But the truth was that for people like themselves – the men and women who have survived an overlooked American opioid epidemic, unnoticed in life as they would probably be in death – the world had become a lonely place, and it was hard to bear the thought of it becoming lonelier.

She sighed, staring at her newly adorned fingers.

“There we go,” she said.

Howell held the phone to her ear.

“Where are you?”

“Hello?”

“Huh?”

“Sam? Sam?”

“Yeah, where are you?”

She listened.

“All right, well you were gone longer, and I was worried. You could have called again.”

She put the phone down. Rogers had said he was on his way back.

Ten more minutes passed.

Howell left the bedroom and, passing beneath the spectral figures of Degas’s dancers, moved to a room at the front of the house that was empty except for packed boxes.

Stepping between them, she took her place at a window and stared out into the darkness, hoping for a glimpse of Rogers – the man whose life she had twice saved – coming home.

– – –

The Washington Post’s Whitney Shefte contributed to this report.

—

Video Embed Code

Video: Sam Rogers and Renee Howell live in fear of their next drug overdose as fentanyl has sent the rate of deaths among African Americans skyrocketing.(Whitney Shefte/The Washington Post)

Embed code:

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments