29 Apr Listening to the Stories of People Who Overdosed

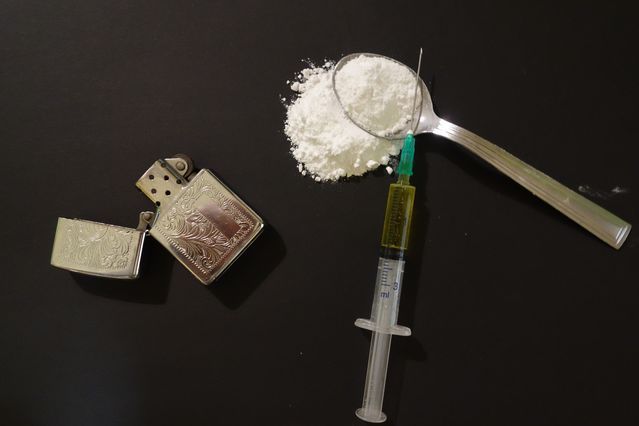

The number of people overdosing on drugs is increasing. In 2017, more than 70,000 people died of an overdose. Many of the overdoses involve a mixture of drugs, with a significant increase in synthetic opioids such as fentanyl that are far more powerful than heroin and other prescription opioid drugs. There is also a marked increase in overdose deaths from cocaine and psychostimulants. In much of the discussion about the “overdose epidemic,” largely missing are voices of those who have overdosed. If drug abuse in general carries stigma, the abuse of certain drugs such as heroin carries even greater stigma. The greatest stigma is reserved for overdosing, especially if one has overdosed multiple times. It is not surprising most people are unwilling to share their stories. Their stories are important, however, for recognizing their humanity even if many cannot understand their behavior. Furthermore, these stories may help physicians and other professionals to understand how drug users view their own behaviors.

An article in The New York Times chronicles Patrick Griffin who overdosed four times in six hours. The first time, he came to on his own. The next three times, emergency responders revived him with naloxone. It took three doses to revive him that final time after which his parents had him involuntarily committed. He was, according to the article, “terrified, angry, and wrung out.” His family was equally terrified and exhausted.

There are not many accounts of what it is like to be brought back with naloxone. As Kevin Jaffray, a long-time former heroin user who now works in drug education describes it,

You are disorientated, confused, weak, and very scared. You just want to sink back into the protective wraparound the heroin brings; you want everything and everyone to just go away. Every piece of you wants to get up and run, and just keep going, but there’s no energy, nothing—total disassociation from reality, with everything around you playing out like a shit reality show in which you’re the unwilling star with nowhere to hide…. I’ve been revived with naloxone five times, and those are the ones that I remember….My life was a cycle made up of prison, hospitals, homelessness, and the constant search for oblivion to take my mind off the pain of living. I guess my fear of living was stronger than my fear of dying. The problem with coming ’round after naloxone is that the brain won’t accept the fact you’ve been dead. It’s almost like a defense mechanism that softens the harsh reality of what’s just happened. And this denial from the truth kicks in and all you want is that medicine to give you oblivion again.

People’s responses to being revived are varied. Some are thoroughly disoriented while others are grateful. Some are indifferent and really do not care one way or the other. There are those who are angry at having been brought back; some wanted to die while others had a good high ruined.

A number of them will shoot up again almost immediately, as Patrick Griffin did. The reasons for using are more varied than the responses to being revived. The reasons for using do not disappear with the administration of naloxone, which only reverses the effects of the drugs. Naloxone neither reduces cravings nor fends off withdrawal symptoms nor eliminates the fear of withdrawal and the fear and pain of living. Many will continue the search for the protective wraparound and the oblivion drugs bring.

To most people who are not addicted, this makes no sense. Even to many who are addicted to other substances or behaviors, this makes no sense. The assumption is that a near-death or actual death experience should scare a person out of this behavior. This raises the question how people could know the risks (having experienced them first hand) but still engage in an activity that could kill them. They may shoot up knowing the heroin is laced with fentanyl. Making it even more incomprehensible is that some heroin users may become resigned or even fatalistic; they know they will die of an overdose eventually. If not this time, then perhaps the next.

Barbara, a former long-term heroin user who is now being treated with medication substitution therapy, was herself brought back multiple times with naloxone and has revived her friends. According to Barbara, witnessing an overdose and trying to reverse it is, “one of worst things in your life. The horror of it.” Someone like Barbara is perhaps the most incomprehensible to many people. She has been on both sides of the administration of naloxone and yet she continued to use, hoping to be smarter and not overdose again.

Emergency Departments in hospitals have become ground zero for overdosing patients thereby providing an opportunity for intervention and treatment. Emergency department physicians may administer buprenorphine, which significantly reduces craving. Not being caught in the grips of craving may have an important two-fold effect. The first is that the attending physician will see a person and not just an overdose. This will have an impact on how the physician or nurse interacts with their patient. Being seen and treated as a person may help some people be more open to information about treatment options. Nothing closes off communication and willingness to listen more than the feeling that one doesn’t matter even if she herself struggles to see her worth.

There is something of a translation or comprehensibility gap as I mentioned above. People including physicians cannot understand why someone keeps engaging in the same potentially dangerous and even deadly behaviors. This is why first person stories of addicts are so important. People who have overdosed and been revived can help to educate physicians and other healthcare providers about the whys and hows of overdosing. They can describe their logic behind using as they do. Addicts do have the ultimate insider knowledge and expertise. They just need to find safe and perhaps anonymous ways to impart this knowledge. Healthcare providers would benefit from listening and seeing the problem “from the inside.”

In 1899, philosopher/psychologist/physician William James confronts his own arrogance and presumptuousness while riding along in a carriage in a rural area. When he sees how many gorgeous trees have been cut down to make almost brutal-looking clearings, he asks is driver who does something like that. The driver responds they all do because they value cultivation and the security it brings. They do it for their families. James can do nothing but confront his own arrogance. He realizes, “neither the whole of truth nor the whole of good is revealed to any single observer….Even prisons and sick-rooms have their special revelations. It is enough to ask of each of us that he should be faithful to his own opportunities and make the most of his own blessings, without presuming to regulate the rest of the vast field.” Emergency rooms have revelations for both overdose victims and physicians if only they could be open to them.

[ad_2]

Source link

No Comments